What a Bat Monitor Can Teach Us About Inclusion

I didn’t realize when I packed my Echo Meter Touch 2 in my luggage that bats would play such an important part in my summer vacation. With just a couple of weeks in Berlin and a few days in Ireland, I thought I’d be lucky if I got a chance to use the bat acoustic detector at all. However, it is so small that it takes up very little room in my suitcase, making it easy to bring it along on my travels.

I also didn’t realize that the joy I took in wielding the acoustic monitor would rile a bat expert from the Netherlands and involve me in a discussion about the role of amateur citizen scientists in conservation, a discussion that was mirrored mere weeks later in the August issue of Nature magazine. In the article, the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) is faulted for seeking to embrace more ”amateur” opinions in their assessment work.

Here’s what happened.

In Berlin we were staying in an apartment near the Volkspark Am Weinberg. The park is a gem of an urban park with children’s play areas, a rose garden that doubles as a beer garden, and a fabulous Swiss restaurant in the middle with decks overlooking a grassy expanse that rolled down toward a small pond over which a grey heron stood sentry. Every evening this grassy area was filled with Berliners enjoying the cool of the evening in the middle of a summer heatwave. This was the scene of my so-called crime: my amateur deployment of the Echo Meter Touch 2.

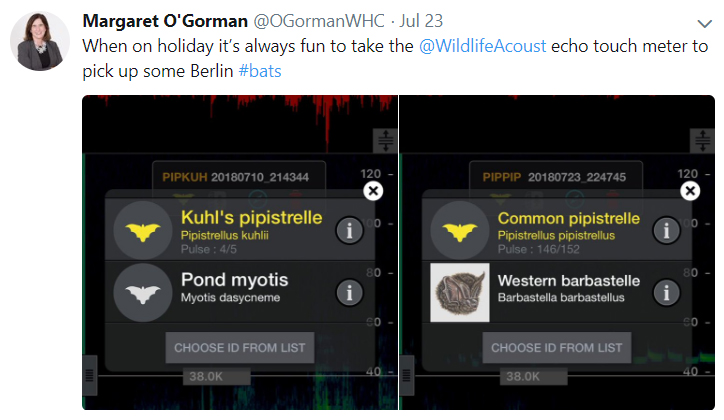

Whenever I have successful “sightings” of bats using the acoustic monitor, I like to post the results on my Twitter feed. I do this to raise awareness about the species around us, whether we are in pristine wilderness or an urban setting. I do it because a bat ”sighting” makes me happy. I do it to encourage others to participate in nocturnal wildlife watching. One of our passions at Wildlife Habitat Council is connecting non-experts to nature and seeing how increased knowledge and ease with the natural world becomes a contagious enthusiasm for conservation. I tweet to create a buzz.

Whenever I have successful “sightings” of bats using the acoustic monitor, I like to post the results on my Twitter feed. I do this to raise awareness about the species around us, whether we are in pristine wilderness or an urban setting. I do it because a bat ”sighting” makes me happy. I do it to encourage others to participate in nocturnal wildlife watching. One of our passions at Wildlife Habitat Council is connecting non-experts to nature and seeing how increased knowledge and ease with the natural world becomes a contagious enthusiasm for conservation. I tweet to create a buzz.

No sooner had I posted my observations of a Kuhl’s pipistrelle and a common pipistrelle than a bat expert criticized the accuracy of the Echo Meter Touch 2 and dismissed the “layman” for having access to such technology and compromising the data collected by experts. He then took the manufacturer of the Echo Meter Touch 2 to task for not moving fast enough in refining their technology. In terms of exchanges in the wild world of Twitter, it was very mild, but it was also unnecessary and indicative of a strain of conservation snobbery that sees only the need to protect the purity of the science without acknowledging the larger picture.

It’s the same argument being made right now on the global stage, where the IPBES is being criticized for adopting an approach called “Nature’s Contribution to People” in their latest assessment efforts, which will involve non-traditional, non-professional and non-western approaches to measuring and valuing biodiversity. In explaining the approach, a delegate to a recent IPBES meeting in Bonn told Nature magazine, “Not everyone who knows about biodiversity or is a custodian of biodiversity is a scientist. We need to learn to listen to people even if they don’t have a PhD.” But not everyone agrees. Vehement argument to the contrary is coming from the economists of natural capital valuation schemes. Their views and approaches have been ascendant for decades, even though the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the primary funding mechanism for UN environment programs, has stated, “Valuation is not leading to the development of policy reforms needed to mitigate the drivers of biodiversity loss and encourage sustainable development through the better management of biodiversity and natural capital, nor is it triggering changes in the use and scale of public and private finance flows on the scale necessary to address threats.” In short, the GEF has concluded that valuation schemes are not the silver bullet for our current crisis.

My critic on Twitter, eco-economists and traditionalists at global conferences all have something in common: a disdain for non-professionals “meddling” in their respective ivory towers. For them, the message has not yet sunk in about the necessity of welcoming the contribution of the layman and understanding that embracing the human dimension can add so much more than the distribution curves and range maps, and that strength comes from having people push policy with science in a supporting role.

Fortunately for me, my second vacation deployment of the Echo Meter Touch 2 in a garden in a small town in Ireland was proof positive of the power of engagement. Three young girls aged 8, 10 and 11 ran wild in a twilit garden screaming “pipistrelle” at the tops of their lungs, having seen the acoustics of a common, soprano and Nathusias’ pipistrelle on the screen of my phone. I know they will add that experience to their collection of summer memories for the future. These girls are unlikely to grow up to be bat experts, but they will grow up to be bat aware.

While we always support and advocate for the PhDs, the professors and the experts, we should never forget to empower and embrace the amateurs, the innovators and the tinkerers. As we move into our Conservation Conference in November, which draws upon both the knowledge of experts and the experiences of laymen, we know that all approaches are needed to protect, restore and recover all species.